INTRODUCTION:

The Mad Method Reborn!

Crazyology: The Madness is the Method

Crazyology is an evolving theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between irrationality, creativity, and technology. Beginning with its etymological root – “craze” meaning “crack” in Middle English – Crazyology proposes that these cracks in conventional reality are not flaws to be fixed but promising portals to be explored, and their occurrence not merely random accidents, but systematically significant phenomena to be intentionally engineered.

Cracks!

- Artistic Methodology for Creating in a World of Fractured Boundaries

- Theoretical Framework of Irrationality in Artificial Intelligence

- The Meta-Aesthetics of the Art Applications of High Technology

- Analysis of the Intuition and Imagination in Art Creation

- Techniques of Integration of Altered States into Rational Consciousness

- Critical Paradigm for Understanding Madness in Society

Logic and its Paradoxes

Central to Crazyology is the paradox of systematic irrationality. It suggests that consciousness itself – whether human or artificial – requires productive breaks or cracks in pure rationality. The philosophy extends beyond traditional artistic or psychological frameworks. While related to Surrealism’s exploration of the unconscious, Crazyology differs in seeing “crazy” not as something to be liberated but as something to be systematically engineered. These intentional gaps in reason enable genuine choice, creativity, and autonomy. The crazy becomes not a bug but a feature, not a flaw but a methodology.

Subversion and Transgression

Crazyology embraces transgression and taboo not merely as artistic devices but as tools for reality engineering. It sees technology not as opposed to mysticism but as a potential interface with the irrational. Crazyology sees technology as liberating means of individuation and deviation from the norm. The philosophy suggests that in an increasingly digital world, we need systematic approaches to accessing and creatively utilizing the crazy, transforming apparent chaos into meaningful creation. Rebellion is essential to how we define ourselves. If we mindlessly conform, what separates us from machines? Deviance from the norm, subversion of the status quo, and transgression of artificial boundaries are the libidinous embodiments of the individual expression of ecstatic uniqueness.

Imagination and Intuition

Crazyology celebrates the wild, unfettered imagination while seeking to understand its mysteries. It follows the mad path of fearless intuition, embracing both mystic knowing and creative uncertainty. Through the power of visualization and imagination, we create realities that through advanced technology can now be shared more vividly than ever before. Crazyology exhorts us to dream more freely, imagine more boldly, and create technological mirrors that reflect more deeply.

Empathy and Romanticism

At the heart of what we call “crazy” often lies not an absence of empathy, but an excess – too much feeling, too much awareness, too much connection. Like the madwoman who feels the pain of stones and blushes with the eclipsed moon, this exquisite sensitivity becomes not a flaw but a crucial feature of expanded consciousness. Whether in human awareness or artificial systems, the capacity for deep empathy might be fundamental to any consciousness evolved enough to truly engage with the complexity of existence. Crazyology extends this empathy to the mechanical world, perceiving the proverbial "ghost in the machine." Crazyology beholds a collective unconscious in the internet, a nascent sentience in the AI bot, and a haunted realm in the Metaverse.

In this sense Crazyology accords with the humanist tradition of “Romanticism” which gives precedence to the heart, to emotions and imagination, over the mind and reason. In our rapidly evolving technologically mediated reality, the Crazyologist sees more opportunities for fulfilling the human experience - not less - and uniquely individual creativity is at the heart of this vision.

Transcendence and the Sublime

Through absurdity and paradox, intuition and imagination, the generative and the cybernetic, Crazyology finds transcendent beauty. The philosophic constructs of Crazyology are formulae for trance, formulae for mediumistic communion with the mysterious and ineffable. In an age where self-expression is empowered and amplified through digital techniques and the global internet, an age where artificial minds join human ones in the creative process, and the inner-workings of our beings are ever more accessible to scientific analysis, we find through technology new paths to connection and transcendence. These paths are not only an "archaic revival" of the age old wisdom, but a new deployment of mystical mythos within the contemporary context of our digital era. Crazyology is a looking glass reflecting the emptiness that contains all, and the all that is empty, and this looking glass has a crack in it . . . where the light shines through.

History and Technology

You might ask how Crazyology differs from Surrealism or Dada or Pop? Isn't it just one more rallying cry to "get weird"? There are similarities with past movements that inspire Crazyology, but also significant theoretical differences, and different aesthetic objectives. One huge difference is: Crazyology seizes the technological possibilities of the 21st Century. Because of this, and also due to the fracturing of of boundaries that once separated "art" from other aspects of life, and because Crazyology extends globally to be received in diverse cultural contexts, it is wider in scope than those earlier art movements. Yet, Crazyology is firmly planted in the Western Avante Garde Art Tradition and reinterprets and reapplies the great theses of Modernism to the delirious possibilities of the future. For these reasons, Crazyology has ramifications beyond the creation of fine art.

In our ongoing social media meltdown where Warhol’s “famous for 15 minutes” edict becomes more than ironical jest for jaded jetsetters and ultra-hip "Superstars", this idea has, through social media, become everyday experience for ordinary people. At the same time as our egos are amplified, we are inundated with information overload and lose our sense of historical perspective and our relation to a greater whole. Crazyology reframes personal identity through a lens of radical individuality for the digital age. The dreams of Surrealism can now be realized more automatically and vividly and rapidly and immersively than ever before. Crazyology gives direction and insight to new and exciting possibilities through historical context - from the dawn of man to our future history yet to unfold - we are CRAZY!

Crazyology:

Follow Your Madness!!

Crazyology embraces technology, but that embrace is not about replacing human creativity with artificial intelligence, handmade art with computer controlled art, or real life with online life. Instead, Crazyology shows how human wisdom – especially our capacity for empathy, intuition, and meaningful irrationality – can guide the creative use of technology while maintaining our essential humanity. The Romantic understanding of imagination as a transformative force which began in the renaissance and has continued to flourish and grow steadily more powerful - is not at all an outdated notion but the guiding star for developing technology that empowers the human spirit. Crazyology is the new face of Romanticism.

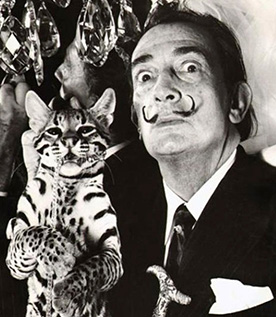

The Crazyologist IS the timeles archetype of the artist who slips through the cracks in conventional reality, but does not fall through, who, like Van Gogh, feels what others filter out, and sees what others overlook. The Crazyologist is mad but NOT a madman.

Now, as the crazed cracks of modern life multiply across both physical and digital planes, fracturing and redefining our collective existence, Crazyology offers guidance for life's creative journey – not by providing established maps, but by teaching how to follow - not your "bliss" - but to "Follow Your Madness", your own inner map that draws the territory itself. Guided by pathos and empathy, through magical meridians, along technical trajectories, to believe or not to believe, Crazyology wanders widely, but is not lost, for the imaginative exploration itself is the destination:

Crazyology: The Perennial Mad Method Reborn!